You do not have to be an accomplished student of history to know that slavery in America was one of the most divisive issues the country faced in the mid-19th century. Eventually, the nation itself split into north and south as did most of the Christian denominations. While the nation was reunited after the War Between the States, many of the religious organizations would remain divided.

Less well known is the fact that while many anti-slavery proponents agreed that slavery was evil, they were far apart in their expectations for erasing that evil. Many, including President Lincoln, sought gradual emancipation of the slaves, and even when freedom was attained these champions of freedom assumed that colonization, preferably in another country, was the most desirable solution.

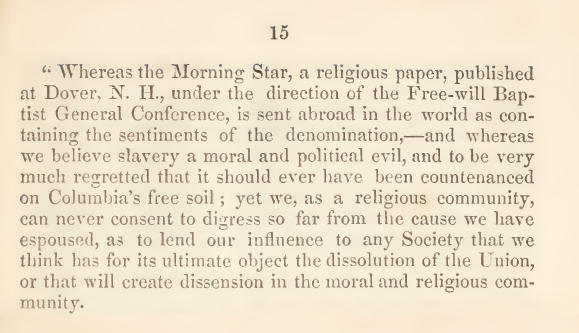

As should be expected, it was Free Will Baptists in New England who spoke out most openly against slavery. In fact, that segment of the denomination found itself on the early, cutting edge of opposition to the practice. An 1834 article in The Morning Star, one of the most popular Free Will Baptist newspapers, condemned slavery as evil, but also expressed the fear that immediate abolition would be an even greater error.

But the next year, in March, the Rockingham Quarterly Meeting of Free Will Baptists boldly called for immediate emancipation of all slaves, arguing that this was the only avenue open to those who accepted the teachings of scripture. When the General Conference met in Byron, New York, in October of that year, the entire New England family of Free Will Baptists added its support to the anti-slavery movement. Unlike other denominations—Baptists, Methodists, Presbyterians—Free Will Baptists did not suffer the grief of formal division. Two factors probably spared this smaller religious group: (1) Free Will Baptists in the South generally were not landowners and subsequently not slave owners, and (2) the Free Will Baptists of New England and those of the South were already in two different denominational organizations, with limited contact between them.

The Fifth Annual Report of the Free Will Baptist (New England) Anti-Slavery Union, in 1851 (pictured above), announced that all ties with the southern group had been severed over the question of slavery. Later, however, the editor admitted that no formal union had ever taken place. Free Will Baptists would have to wait another three-quarter of a century to find peace and unity, and that only after most of the Randall movement merged with the Northern Baptists in 1910-11.

About the Writer: William F. Davidson was professor of Church History at Columbia International University, in Columbia, South Carolina. Dr. Davidson is an alumnus of Peabody College, Welch College, Columbia Bible College, Northern Baptist Seminary, and New Orleans Baptist Seminary. The Ayden, North Carolina, native also served as pastor of Free Will Baptist churches in Kentucky and Virginia.